Samahope

Head of Design (2012 – 2015)

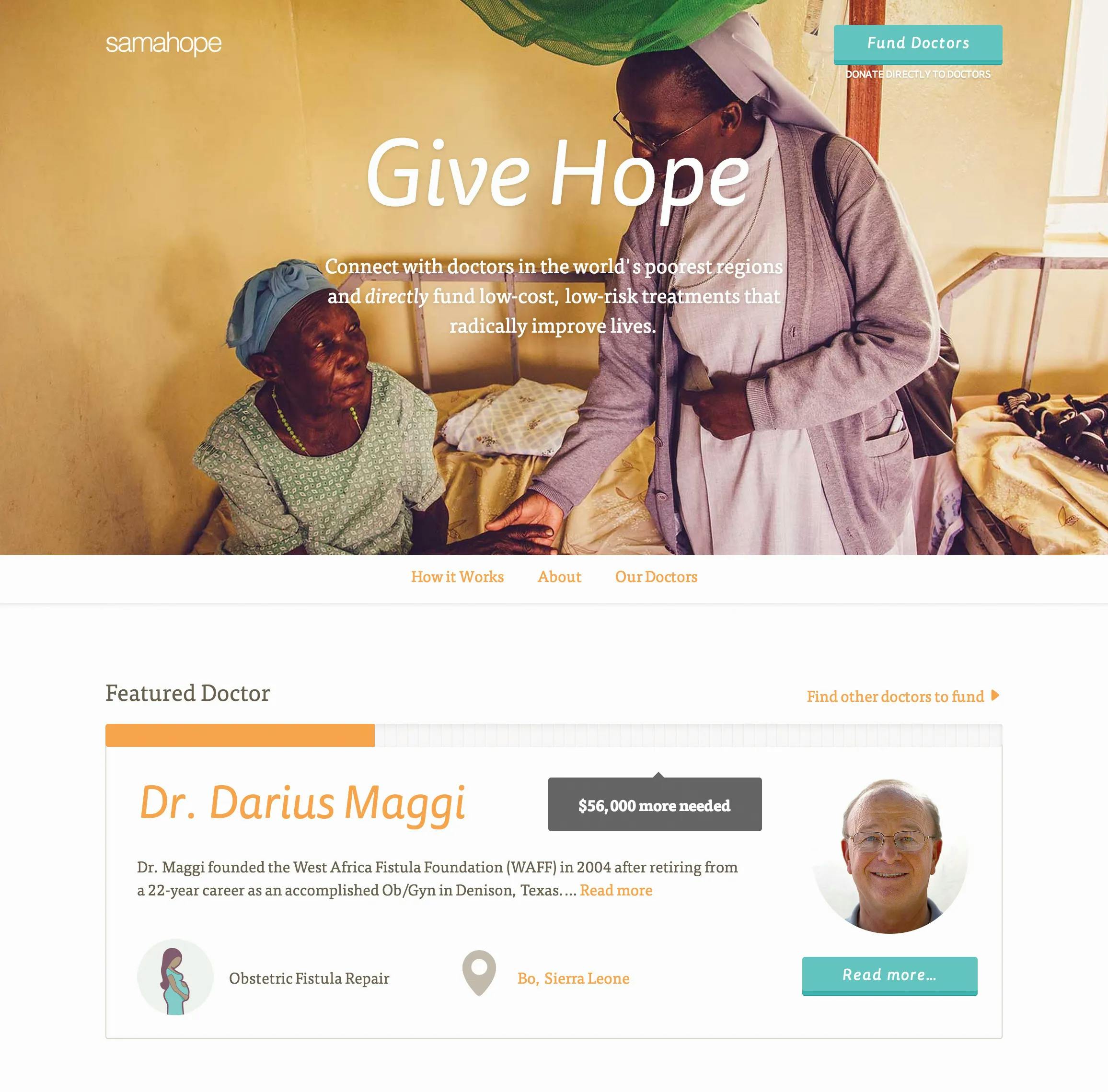

I was the Head of Design for a non-profit startup spun out of Samasource (now Sama), a non-profit that provided employment and workforce development for people in developing economies. Samahope has since been acquired by The Johnson & Johnson Foundation. During its operations, we were able to provide life-saving medical care for tens of thousands of patients.

My Role

As the Head of Design, I worked closely with the founder of the organization to craft a brand and web presence that strove to strike a balance between respecting the dignity and privacy of the patients, while also maximizing donation dollars going to the doctors providing life-saving treatment. All of the doctors on our platform were vetted extensively as humanitarians working in massively underresourced areas. In some cases, they were the only qualified surgeons for a population in the millions, working tirelessly to save countless lives. It was an incredibly challenging role to tell the most unbelievable stories in a way that was believable to people in developed economies who have little personal experience in environments like these.

As part of my role, I was able to do field research in Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda to interview some of our doctors, patients, and catalog some of the outcomes that resulted from donations.

This is a handful of the skills I regularly practiced in this role:

Designed all user flows, web UI, & design system.

Collaborated with founders to set overall product vision.

Conducted international field research to understand the needs of our doctors.

Rapid prototyping to quickly get feedback from donors, medical experts, and doctors.

Led a rebrand, designing the logo and brand voice to evolve the early brand prototype.

All initial development for a full web-based donation platform, using PHP, React, and CSS.

The Challenge

This was an incredibly difficult role for a lot of reasons. As a non-profit, we had very few resources and I accepted the job with a significant paycut. We had to make a very creative use of our budget, and were constantly hunting for more funding since we operated on the "100%" model, where 100% of a donor's dollars go directly to the doctors and patients. The burden fell on us to raise external funds to operate our organization. There was no work/life balance to speak of.

The other massive challenge was designing for something so. incredibly. depressing. Many patients were in truly horrific or life-threatening circumstances, and I had to confront that every day at work. However, we were telling stories of hope; of individuals doing literally heroic work saving countless lives for no pay and very little appreciation. We felt strongly that we should protect the dignity and privacy of patients, which is why the site was structured around funding the doctors doing the work.

My Approach

I had to be incredibly creative and scrappy. For the first year, we were a team of four and I was in charge of all design, product, and engineering. I used open-source web frameworks and libraries wherever I could to save time and money, and focused on telling the most compelling story of the doctors I could.

I knew that I couldn't reasonably design for a situation that I had no personal experience with, so I traveled to Eastern Africa where there was a concentration of doctors we worked with. I toured refugee camps, rural clinics, and catholic missions where the medical care was taking place. I spoke with doctors and patients alike to understand the scope of the problem that was being addressed.

The Doctor's Story

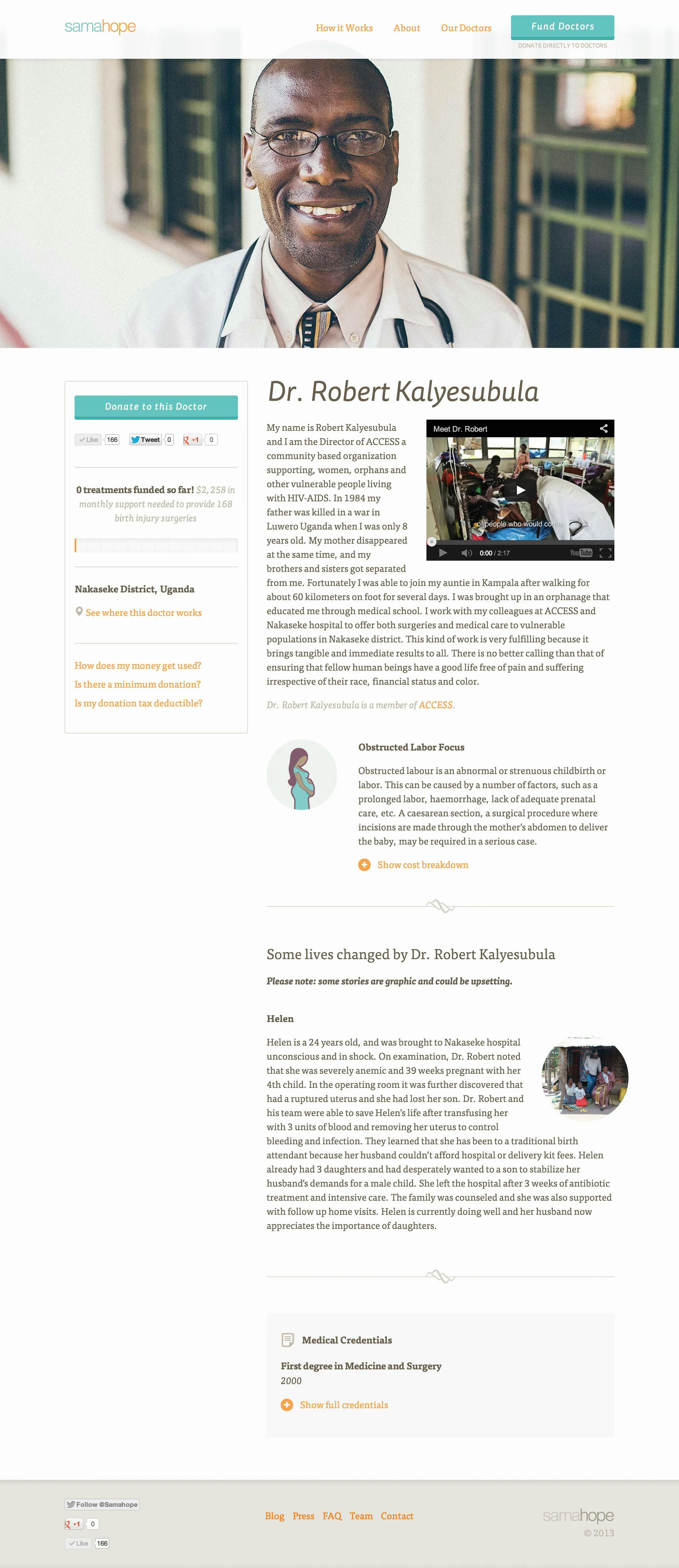

The meat of the donation experience was the doctor's story. These doctors were not using the funds for themselves, but for life-saving medical interventions for their patients. Donations funded even simple things that were not typically available, like hand sanitizer for surgery.

It was incredibly challenging to tell such harrowing stories in a way that allowed people in more comfortable circumstances to connect to them. A further difficulty is that these doctors were often very hard to contact. They worked in very rural areas, often without cell service for days on end.

One of the hardest things to wrap my head around was how costly it was for the doctors to take even a short break to jump on a call with us to tell their story or provide photos for their profile. They were often the only surgeon available for hundreds of miles, and when they take breaks, people die. These doctors worked grueling hours with no vacation. The most amazing thing is that many of them (such as Dr. Robert, pictured below), were trained at top medical schools in the US and could have chosen a very cushy life doing plastic surgery in beverly hills. Instead, they chose to go where they were needed most.

Reflections

This was by far the most rewarding and inspiring work I have ever had the opportunity to do. It can be hard to feel connected to the work we do in tech, but that was not a problem in this role. I met some truly incredible people that have given me undying hope in humanity.

I also learned a lot about non-profit business models. My big takeaway is that this business model is incredibly counterproductive and outdated, and actively wears down the people who want to do the most good. Institutional funders were hard to court, and often had unreasonable strings attached to the money they would provide. Even when everyone had virtuous intentions, the system was not set up to incentivize the most good.

Despite my frustrations with the non-profit business model and the grueling work/life balance I had in this role, it remains one of my most fulfilling roles I have ever held.